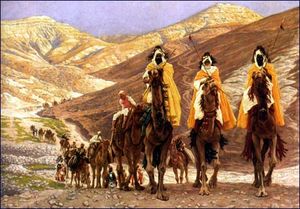

In Christian tradition the Magi, also known as the Three Wise Men, The Three Kings, or Kings from the east, are Zoroastrian judicial astrologers or magi from Ancient Persia who according to the Gospel of Matthew came "from the east to Jerusalem", to worship the Infant Jesus, whom they describe as the Christ "born King of the Jews". According to Matthew, they followed a star, and as they approached Jerusalem, Herod tried to trick them into revealing where Jesus was, but once they had found Jesus they left by a different route. According to Matthew, upon finding Jesus, the magi gave him an unspecified number of gifts, amongst which are three highly symbolic ones.

Contents |

The nature of the magi

Unlike Luke, Matthew pays no attention to the actual birth of Jesus, focusing instead on what occurred before and after. Skipping the actual birth, Matthew introduces a group of people, the Magi, who have come to pay their respects, while accidentally informing Herod of Jesus' existence.

The word Magi is a transliteration of the Greek magos (μαγος pl. μαγοι), which is a derivative from Old Persian Magupati. The term is a specific occupational title referring to the priestly caste of a distorted form of Zoroastrianism, known as Zurvanism. As part of their religion, these priests paid particular attention to the stars, and gained an international reputation for astrology, which at that point was a highly regarded science, only later giving rise to aspects of mathematics and astronomy, as well as the modern practice of fortune telling going by the same name. A clearer indication of their astrological credentials is in the phrase translated in the King James Version of the Bible as enquired of them diligently, which is actually a Greek technical word referring directly to astrology, with no direct translation into English. Their religious practices and astrology caused derivatives of the term magi to be applied to the occult in general, namely this is the origin of the word magic.

The KJV translation as wise men is considered somewhat politically motivated; the exact same word is translated as sorcerer to condemn "Elymas the sorcerer" in Acts 13, and is left untranslated to describe Simon Magus in Acts 8. Treating Simon Magus as being as wise as the Magi that visited Jesus would effectively be heresy - Simon Magus was considered by most Christians as the arch-heretic and founder of Gnosticism, a Christian group condemned as arch-heresy. It is unlikely that the New Testament would deliberately refer to Simon Magus in glowing terms. The modern term simony derives from the name of Simon Magus.

The phrase from the east is the only information Matthew provides on where the magi came from, apart from identifying that they come from their own country rather than Judea. Traditionally the view developed that the magi were Persian or Parthian, a view held for example by John Chrysostom, and historic art works generally depicted them in Persian dress. The main support for this is that the first magi were from Persia and that land still had the largest number of them. Some believe they were from Babylon, which was the centre of Zurvanism, and hence astrology, at the time. Brown comments that the author of Matthew probably didn't have a specific location in mind and the phrase from the east is for literary effect and added exoticism.

Though the Bible does not number the Magi, traditionally there were always seen to be three, as there were three gifts given to the child. However, the text also states that other gifts were given, making the number of Magi even less definite.

Names

In the Eastern church a variety of different names are given for the three, but in the West the names have been settled since the eighth century as Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar. The names of the Magi derive from an early sixth Century Greek manuscript in Alexandria, translated into the Latin Excerpta Latina Barbari. The Latin text Collectanea et Flores continues the tradition of three kings and their names and gives additional details of their clothes, coming from Syria. This text is said to be from the 8th century, of Irish origin. In the Eastern churches, Ethiopian Christianity, for instance, has Hor, Karsudan, and Basanater, while the Armenians have Kagbha, Badadakharida and Badadilma (cf. Acta Sanctorum, May, I, 1780 and Concerning The Magi And Their Names).

None of these names are obviously Persian or are generally agreed to carry any ascertainable meaning, although Caspar is also sometimes given as Gaspar, a variant of the Persian Jasper Rustaham-Gondofarr Suren-Pahlav of the Suren-Pahlav Clan, the ruler of the eastern-greater Iran, who ruled between 10BC to AD17, ruling the vast empire of the Saka at the time of Arsacid dynasty. Another candidate for the origin of the name Caspar appears in the Acts of Thomas as Gondophares (AD 21-c.47) i.e. Gudapharasa (from which 'Caspar' derives via the contrived corruption 'Gaspar'). This Gondophares was also a Suren, and declared independence from Parthia to become the first Indo-Parthian king; he is thus likely to be a descendant of the Rustaham-Gondofarr, who was allegedly visited by Thomas the Apostle. Christian legend may have chosen Gondofarr simply because he was an eastern king living in the right time period.

In contrast, the Syrian Christians name the Magi Larvandad, Gushnasaph , and Hormisdas. These names have a far greater likelihood of being originally Persian, though that does not, of course, guarantee their authenticity.

The first name Larvandad is a combination of Lar, which is a region near Tehran, and vand or vandad which is a common suffix in Middle Persian meaning "related to" or "located in". Vand is also present in the names of such Iranian locations as Damavand, Nahavand, Alvand, and such names and titles as Varjavand and Vandidad. Alternatively, it might be a combination of Larvand meaning the region of Lar and Dad meaning "given by". The latter suffix can also be seen in such Iranian names as "Tirdad", "Mehrdad", "Bamdad" or such previously Iranian locations as "Bagdad" ("God Given") presently called Baghdad in Iraq. Thus, the name simply means born in or given by Lar.

The second name, Hormisdas is a variation of the Persian name Hormoz which was Hormazd and Hormazda in Middle Persian. The name referred to the angel of the first day of each month whose name had been given by the supreme God (of Zoroastrianism) who, in old Persian, was called "Ahuramazda" or "Ormazd".

The third name Gushnasaph was a common name used in Old and Middle Persian. In Modern Persian, it is Gushnasp or Gushtasp. The name is a combination of Gushn meaning "full of manly qualities" or "full of desire or energy" for something and Asp, Modern Persian Asb, which means horse. As all scholars of Iranian studies know, horses were of great importance for the Iranians and many Iranian names including the presently used Lohrasp, Jamasp, Garshasp, and Gushtasp contain the suffix. As a result, the second name might mean something like "as energetic and virile as a horse" or "full of desire for having horses". Alternatively, Gushn is also recorded to have meant "many". Thus, the name might simply mean "the Owner of Many Horses".

Tombs

Marco Polo claimed that he was shown the three tombs of the Magi at Saveh south of Tehran in the 1270s:

- "In Persia is the city of Saba, from which the Three Magi set out and in this city they are buried, in three very large and beautiful monuments, side by side. And above them there is a square building, beautifully kept. The bodies are still entire, with hair and beard remaining." (Book i).

AA Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral, according to tradition, contains the bones of the Three Wise Men. Reputedly they were first discovered by Saint Helena on her famous pilgrimage to Palestine and the Holy Lands. She took the remains to the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople; they were later moved to Milan, before being sent to their current resting place by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I in 1164. The Milanese celebrate their part in the tradition by holding a medieval costume parade every 6 January.

A version of the detailed elaboration familiar to us is laid out by the 14th-century cleric John of Hildesheim's Historia Trium Regum ("History of the Three Kings"). In accounting for the presence in Cologne of their mummified relics, he begins with the journey of Saint Helena, mother of Constantine the Great to Jerusalem, where she recovered the True Cross and other relics:

- "Queen Helen...began to think greatly of the bodies of these three kings, and she arrayed herself, and accompanied by many attendants, went into the Land of Ind...after she had found the bodies of Melchior, Balthazar, and Casper, Queen Helen put them into one chest and ornamented it with great riches, and she brought them into Constantinople...and laid them in a church that is called Saint Sophia."

The gifts of the magi

Upon meeting Jesus, the magi are described as handing over gifts and "falling down" in joyous praise. The use of the term "falling down" more properly means lying prostrate on the ground, which, together with the use of kneeling in Luke's birth narrative, had an important effect on Christian religious practice. Previously both Jewish and Roman tradition had viewed kneeling and prostration as undignified (although for Persians it was a sign of great respect, often showed to the king), but inspired by these verses, kneeling and prostration were adopted in the early church; while prostration is generally no longer featured, kneeling has remained an important element of Christian worship to this day.

Three of the gifts are explicitly identified in Matthew - gold, frankincense and myrrh - and have become one of the best known items from Matthew; it is often assumed that these three are the only gifts the Magi are described as giving. (It has been suggested by biblical scholars that the "gold" was in fact in a medicinal form rather than as metal.) They are often linked to chapter 60 of the Book of Isaiah and to Psalm 72. Both of these report gifts being given by kings, and this has played a central role in the inaccurate perception of the magi as kings, rather than as astronomer-priests. In a hymn of the late 4th-century Iberian poet Prudentius, the three gifts have already gained their medieval interpretation as prophetic emblems of Jesus' identity, familiar in the carol "We Three Kings" (John Henry Hopkins, Jr., 1857).

Many different theories of the meaning and symbolism of the gifts have been advanced, since while gold is fairly obviously explained, frankincense, and particularly myrrh, are much more obscure. They generally break down into two groups:

- That they are all ordinary gifts for a king - myrrh being commonly used as an anointing oil, frankincense as a perfume, and gold as a valuable.

- That they are prophetic - gold as a symbol of kingship on earth, frankincense (an incense) as a symbol of divine authority, and myrrh (an embalming oil) as a symbol of death. Sometimes this is described more weakly as gold symbolizing virtue, frankincense symbolizing prayer, and myrrh symbolizing suffering.

John Chrysostom suggested that the gifts were fit to be given not just to a king but to God, and contrasted them with the Jews' traditional offerings of sheep and calves, and accordingly, Chrysostom asserts that the magi worshipped Jesus as God. This is, however, unlikely, since the magi were magi - a type of zoroastrian priest. C.S. Mann has advanced the theory that the items were not actually brought as gifts, but were rather the tools of the magi, who typically would be astrologer-priests. Mann thus sees the giving of these items to Jesus as showing that the magi were abandoning their practices by relinquishing the necessary tools of their trade, though Brown disagrees with this theory since the portrayal of the magi had been wholly positive up to this point with no hint of condemnation. An alternative reading on the same lines is that the magi gave the tools of their craft to Jesus to acknowledge him as one of them; magi were near universally regarded at the time as being particularly wise, partly owing to their dedication to astrology, and the perception that zoroastrians were always honest, owing to their religion, and hence by adding magi endorsing Jesus as their equal, the author of Matthew was seeking to raise Jesus' own standing.

The gifts themselves have also been criticized as mostly useless to a poor carpenter as his family, and this is often the target of comic satire in television and other comedy. Clarke states that the deist Thomas Woolston once quipped that if they had brought sugar, soap, and candles they would have acted like wise men. What subsequently happened to these gifts is never mentioned in the scripture, but several traditions have developed. One story has the gold being stolen by the two thieves who were later crucified alongside Jesus. Another tale has it being entrusted to and then misappropriated by Judas. Another story is that the family quickly pawned/sold them and later used the money to finance their flight to Egypt.

In the Monastery of St. Paul of Mount Athos there is a 15th century golden case containing purpotedly the Gift of the Magi. It was donated to the monastery in the 15th century by Maro, daughter of the King of Serbia George Vragovitch, wife to the Ottoman Sultan Murat II and godmother to Mehmet II the Conqueror (of Constantinople). Aparently they were part of the relics of the Holy Palace of Constantinople and it is claimed they were displayed there since the 4th century AD. After the Athens Earthquake of September 9, 1999 they were temporarily displayed in Athens in order to strengthen faith and raise money for earthquake victims.

At this point the magi leave the narrative by returning another way so as to avoid Herod, and do not reappear. Gregory the Great waxed lyrical on this theme, commenting that having come to know Jesus we are forbidden to return by the way we came. There are many traditional stories about what happened to the magi after this, with one having them baptised by St. Thomas on his way to India. Another has their remains found by Saint Helena and brought to Constantinople, and eventually making their way to Germany and the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral. Marco Polo in his writings claimed that he saw their perfectly preserved bodies in Saveh in Persia on his journeys.

Herod

When the magi first enquire about Jesus, Matthew says that they were overheard by "Herod the King", who is accepted to refer to Herod the Great who died in 4 BC. This is seemingly in contradiction with Luke's mention of a census and of Quirinius being governor of Syria, which both apply to some time after 6 A.D. The magi claim to wish to pay homage (proskunesai in the Greek) to a King of the Jews. While proskunesai can mean honouring either a king or a God, King of the Jews is a clear and direct challenge to Herod's authority. Herod was renowned for his paranoia, killing several of his own sons who threatened him. As an Edomite, Herod would be especially threatened by a Davidic heir, who would automatically be more in favour with Jewish fundamentalists of the time, who had a particularly xenophobic attitude.

Why all Jerusalem should be troubled by an opponent to Herod is a more important question. Throughout this chapter Matthew shows the leaders of Jerusalem allied with Herod against Jesus, and so these passages have often been quoted in support of Christian anti-Semitism. That all Jerusalem is agitated also seems to conflict with later passages in the same Gospel, where the people are quite oblivious to Jesus' existence. Gundry sees this passage as influenced by the politics of the time it was written, as a foreshadowing of the rejection of Jesus and his church by the leaders of Jerusalem. Brown notes that another option, supported even in ancient times by John Chrysostom, is that Matthew is trying to portray Jesus as a new Moses; in Exodus all Egypt is troubled by Moses, not just the Pharaoh. Levin believes in a third option which sees Matthew as presenting a class war throughout his Gospel, with Jesus on the side of the poor and nomadic, against powerful city dwellers.

Most scholars take the reference to all the chief priests and scribes as referring to the Sanhedrin, however, there is a difficulty in taking this literally as there was only one chief priest at the time, so all the chief priests can only literally refer to a single individual. Taking it less literally, Brown notes that this phrase occurs in other contemporary documents, and refers to the leading priests and former chief priests, not only the current head of the priesthood. A more important difficulty with this passage is its historical implausibility, since records from the period show that Herod and the Sanhedrin were sharply divided, and their relations acrimonious. At the time the priests were largely Sadducees while the scribes were mostly Pharisees, thus both groups being present might be a deliberate attempt to tar both leading Jewish factions as being involved with Herod. Schweizer states that Herod consulting with the Sanhedrin is historically almost inconceivable, and he views their presence in the passage merely as a literary device to have someone able to subsequently quote an Old Testament prophecy.

After having consulted with these religious individuals, Herod is described as secretly meeting with the magi, which while fitting with Herod's paranoid nature, does beg the question of how Matthew could possibly have known that the events took place. Subsequently, Herod is described as sending the magi to Bethlehem to discover where Jesus is, so that he can worship him. Many scholars, such as Brown and Schweizer, find it improbable for this passage to be factual; Bethlehem is only five miles from Jerusalem and it is thus odd that Herod would need to use foreign priests that he had only just met for such an important task, trusting them implicitly despite his usual paranoia, even though he could easily give the task to his soldiers or others more trusted by him. France defends the historicity of this story, theorising that soldiers might alarm the villagers, making it difficult to find the infant, though searching a village only five miles away, even with deeply distrusting villagers, isn't that difficult a task when you have an entire army at your disposal. France has also proposed that Herod chose the magi to carry the task out since they were more likely to be gullible, as foreigners, or at least have less qualms than Jewish soldiers would about killing someone supposedly fitting a Jewish prophecy.

The birthplace

This narrative of the visit of the Magi is the first point in Matthew that Bethlehem, the place of Jesus' birth, is mentioned. That it is specified as being in Judea is ascribed by Albright and Mann to emphasise that it isn't the northern town also named Bethlehem (probably the modern town of Beit Lahna), though other scholars feel the main purpose of this mention is to assert that Jesus was born in the heart of Judaism and not in the unrespected backwater that was Galilee. According to the chronology in Luke, the family left Bethlehem soon after arriving, when Jesus was forty days old, but according to Matthew, the Magi visited Jesus in Bethlehem when he was at a house. This raises the question of how the family has its own home in the town when the magi vist, having only been able to have a stable when Jesus was born.

Most modern scholars believe that the author of Matthew is fairly clear in this chapter that the family had lived for some time in the town, and was likely originally from Bethlehem, thus it is logical for them to have a house. This reading does contradict Luke's story of the emergency trip to the town, however, a view which those who believe in the inerrancy of the Bible naturally do not feel able to support. These inerrantists instead believe that either that the couple found a house very quickly, i.e. in less than forty days, while Mary had only just given birth, or that, contrary to the views of almost all scholars of linguistics, house should be translated instead as village. Those not willing to accept that one of the two gospels is outright wrong, but still willing to accept that Matthew and Luke cannot be exactly synchronised, generally feel that the magi visited several months after the birth of Jesus, and Luke has got wrong the length of time that the family stayed in Bethlehem.

Another theory is that the Magi visited about two years after the birth of Jesus, explaining why Herod, thwarted in his plans, to later order the death of children aged two years and below to be slaughtered. For many, especially believers in inerrancy, this settles the seeming contradiction.

The magi are described as having followed a star, which traditionally became known as the Star of Bethlehem, since that is where it led them to. Since at least Kepler there has been much work to try and link it to an astronomical event, with the most common cited being a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 7 BC, fitting in with Matthew's chronology pointing to Jesus being born before 4 B.C., unlike Luke's which points to 6 A.D.. Although traditionally the magi are described as having seen a star in the east, the Greek word in question is anatole, which many scholars feel more accurately translates as a star risingg.

John Chrysostom rejected the idea that the Star of Bethlehem was a normal star or similar heavenly body, because such a star could not have specified the exact cave and manger where Jesus was found, being too high in the sky to be that specific. Also, he notes that stars in the sky move from east to west, but that the magi would have travelled from north to south to arrive in Palestine from Persia. Instead, Chrysostom suggested that the Star was a more miraculous occurrence, comparable to the pillar of cloud mentioned in Exodus as leading the Israelites out of Egypt. In the Byzantine tradition, influenced by Chrysotom's writing and palace etiquette, the star was interpreted as a palace official that led the foreign dignitaries to the king, and as such is depicted in Byzantine art

In Matthew 2:9 it states that the star came and stood over where Jesus was, seemingly stating that the star pointed out the specific house or village that Jesus was in. Quite how it did this is unspecified in the text, and artists have portrayed a wide array of means. Hill comments that the star standing over a fixed location is an undeniably miraculous action which defies all attempts to rationalize the star as a natural nova or conjunction. However, it is perfectly possible for a previously moving star or conjunction to appear to halt its location in the sky - the sun freezes in its annual north-south motion for three days twice a year, at the winter and summer solstice (co-incidentally due to precession of the equinoxes, 25 December was the winter solstice at the time).

Astronomer Michael R. Molnar and others have taken the view that Matthew's statements that the star "went before" and "stood over" are terms that refer respectively to the retrogradation and stationing of the royal "wandering star" Jupiter. If Molnar's research is correct, this would require the birth to have taken place on 17 April, 6 BC, and the standing over on 19 December, and the magi would have had to arrive at some point thereafter.

At the time the notion of new stars as beacons of major events were common, being reported for such figures as Alexander the Great, Mithridates, Abraham, and Augustus. Pliny even takes time to rebut a theory that every person has a star that rises when they are born and fades when they die, evidence that this was believed by some. According to Brown, to many at the time it would have been unthinkable that a messiah could have been born without some stellar portents beforehand.

According to John Mosley, the program supervisor for Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, the key question is whether the account refers to "stars" or "planets". The distinction is not likely to have been meaningful to astrologers like the Magi in the first century AD. If it was a planet then there are a number of celestial events that would have attracted the interest and fascination of anyone, like the Magi, who followed the stars. Mosley argued:

- Historical records and modern-day computer simulations indicate that there was a rare series of planetary groupings, also known as conjunctions, during the years 3 B.C. and 2 B.C.

- On the morning of June 12 in 3 BC Venus could be sighted very close to Saturn in the eastern sky

- On August 12 in 3 BC there was a spectacular pairing of Venus and Jupiter in the constellation of Leo, which ancient astrologers associated with the destiny of the Jews

- Between September in 3 BC and June in 2 BC, Jupiter's retrograde motion caused it to appear to deviate from its path and loop around Regulus, a star in Leo. Astrologers considered Jupiter the kingly planet and regarded Regulus as the king star. This ties in with evidence of an October birthdate for Jesus.

- On June 17 in 2 BC, Jupiter could be sighted so close to Venus that with a naked eye they appeared to have merged

- On December 28 in 3 BC, all the planets formed the shape of the Star of David.

Mosley's claims have been disputed by several astronomers as contrived, and inaccurate, for example, his claim that a cross shaped arrangement of the planets was the star fails to appreciate that the cross only became considered a Christian symbol in the 6th century. David Turner, professor of astronomy at St Mary's University, has argued extensively against Mosley's conclusions, and has stated that some of the claims are extremely tenuous. The date of Herod's death is generally accepted to be 5-4 BC, which would be before these astronomical events of 3-2 B.C. In other words, Jesus was born, the Magi visited Herod, and went to Jesus, Herod caused Jesus to flee, and only then did the stars begin an astronomical event that had highly symbolic significance; suggesting that if that was indeed an event indicating the Messiah's birth, then the Messiah was an unknown individual born 1-2 years after Jesus.

Some Christians have had difficulty with reference to the star as elsewhere in the Bible astrology is condemned, a view shared by most fundamentalist Christians. Consequently, R.T. France has argued that the passage is not an endorsement of astrology, but rather an illustration of how God takes care in meeting individuals where they are.

Other Christians interpret the star as a fulfilment of the "Star Prophecy" in the Book of Numbers:

- There shall come a star out of Jacob, and a sceptre shall rise out of Israel, and shall smite the corners of Moab, and destroy all the children of Sheth - Numbers 24:17

The Bethlehem prophecy

The text describes the magi explaining to Herod about the purpose of their visit by use of a quote from the prophet:

- But you, Bethlehem Ephrathah, though you are little among the thousands of Judah, out of you will come for me one who will be ruler over Israel, whose origins are from of old, from ancient times - Micah 5:1-3 (according to the Masoretic text)

The quotation given in Matthew is from the Book of Micah (5:1-3), though it differs substantially from both the Septuagint and Masoretic texts of the same passage. The Septuagint and Masoretic refer to Bethlehem as Bethlehem Ephratah, which Matthew alters to Bethlehem, land of Judah, apparently to further emphasise that Jesus was born in Judea not Galilee, where he spent much of his ministry, an area that was viewed by most religious Jews as being unclean and lower than the half-cast people in the intermediate region. An even more important change is the almost total inversion of the meaning - Micah has you are little among the thousands of Judah whereas Matthew's quote of it has you are not least among the princes of Judah.

Matthew also replaces the word ruler with shepherd, apparently to present the argument that a messiah would be a religious figure rather than a political one. The portion of Micah where this quote is found is clearly discussing a messiah and states that like King David, the messiah would originate from Bethlehem. At the time it was not widely accepted that the messiah would necessarily be born in Bethlehem, just that his ancestors would have been, and thus it was not considered essential for a messiah to be someone born in that town, although it was considered a reasonable area for one to happen to originate from. Certainly far more reasonable than the peripheral area of Galilee where Jesus grew up.

Religious significance

According to most forms of Christianity, the Magi were the first religious figures to worship Christ, and for this reason the story of the Magi is particularly respected and popular among many Christians. The visit of the Magi is commemorated by Catholics and other Christian sects (but not the Eastern Orthodox) on the observance of Epiphany, January 6. The Eastern Orthodox celebrate it on December 25 along with Christmas. This visit is frequently treated in Christian art and literature as The Journey of the Magi.

Upon this kernel of information Christians embroidered many circumstantial details about the magi. One of the most important changes was their rising from astrologers to kings. The general view is that this is linked to Old Testament prophesies that have the messiah being worshipped by kings in Isaiah 60:3, Psalm 72:10, and Psalms 68:29. Early readers reinterpreted Matthew in light of these prophecies and elevated the magi to kings. Mark Allan Powell rejects this view. He argues that the idea of the magi as kings arose considerably later in the time after Constantine and the change was made to endorse the role of Christian monarchs. By 500 A.D. all commentators adopted the prevalent tradition of the three were kings, and this continued until the Protestant Reformation.

Though the Qur'an omits Matthew's episode of the magi, it was well known in Arabia. The Muslim encyclopaedist al-Tabari, writing in the 9th century, gives the familiar symbolism of the gifts of the magi; he gives as his source the later 7th century writer Wahb ibn Munabbih. [1]

This positive interpretation of the Magi is not unopposed. The Jehovah's Witnesses [2] do not see the arrival of the Magi as something to be celebrated, but instead stress the Biblical condemnation of sorcery and astrology in such texts as Deuteronomy 18:10-11, Leviticus 19:26, and Isaiah 47:13-14. They also point to the fact that the star seen by the Magi led them first to a hostile enemy of Jesus, Herod, and only then to the child's location - the argument being that if this was an event from God, it makes no sense for them to be led to a ruler with intentions to kill the child before taking them to Jesus.

Traditions of the Epiphany

- Holidays celebrating the arrival of the magi traditionally recognise a sharp distinction between the date of their arrival and the date of Jesus' birth. Matthew's introduction of the magi gives the reader no reason to believe that they were present on the night of the birth, instead stating that they arrived at some point after Jesus had been born, and the magi are described as leading Herod to assume that Jesus is up to 1 year old.

- Christianity celebrates the Magi on the day of Epiphany, January 6, the last of the twelve days of Christmas, particularly in the Spanish-speaking parts of the world. In these Spanish-speaking areas, the three kings (Sp. "los Reyes Magos de Oriente", also "Los Tres Reyes Magos", receive wish letters from children and magically bring them gifts on the night before Epiphany. According to the tradition, the Magi come from the Orient on their camels to visit the houses of all the children; much like the Northern European Santa Claus with his reindeer, they visit everyone in one night. In some areas, children prepare a drink for each of the Magi, it is also traditional to prepare food and drink for the camels, because this is the only night of the year when they eat.

- Spanish cities organize cabalgatas in the evening, in which the kings and their servants parade and throw sweets to the children (and parents) in attendance. The cavalcade of the three kings in Alcoi claims to be the oldest in the world; the participants who portray the kings and pages walk through the crowd, giving presents to the children directly.

- In France, the holiday on January 6 is celebrated with a special tradition: within a family, a cake is baked which contains one single bean. Whoever gets the bean is "crowned" king for the remainder of the holiday.

The Magi depicted in art

The Magi most frequently appear in European art in the Adoration of the Magi; less often The Journey of the Magi topos. More generally they appear in popular Nativity scenes and other Christmas decorations that have their origins in the Neapolitan variety of the Italian presepio or Nativity crèche; they are featured in Menotti's opera Amahl and the Night Visitors, and in several Christmas carols, of which the best-known English one is "We Three Kings". Artists have also allegorised the theme to represent the three ages of man. Since the Age of Discoveries, the Kings also represent three parts of the world in western art. Balthasar is thus represented as a young African or Moor and Caspar may be depicted with distinctive Oriental features. In Orthodox Art they are depicted as Persians

An early Anglo-Saxon picture survives on the Franks Casket, probably a non-Christian king’s hoard-box (early 7th century, whalebone carving); or rather the hoard-box survived Christian attacks on non-Christian art and sculpture because of that picture.. In its composition it follows the oriental style, which renders a courtly scene, with the Virgin and Christ facing the spectator, while the Magi devoutly approach from the (left) side. Even amongst non-Christians who had heard of the Christian story of the Magi, the motif was quite popular, since the Magi had endured a long journey and were generous. Instead of an angel, the picture places a swan, interpretable as the hero's fylgja (a protecting spirit, and shapeshifter).

In the film Donovan's Reef, a Christmas play is held in French Polynesia. However, instead of the traditional correspondence of Magi to continents, the version for Polynesian Catholics features the king of Polynesia, the king of America, and the king of China.

Further sentimental narrative detail was added in the novel and movie Ben-Hur, where Balthasar appears as an old man, who goes back to Palestine to see the former child Jesus become an adult.

According to Howard Clarke, in the United States, Christmas cards featuring magi outsell those with shepherds.

See also

- In the video game Chrono Trigger, the three wise men: Belthasar, Gaspar, and Melchior help the main characters in various ways throughout their journey through time in order to stop the destruction caused by Lavos.

- In the TV Anime Neon Genesis Evangelion, the names of the three supercomputers in NERV correspond to the three Magi.

Referencess

- Albright, W.F. and C.S. Mann. "Matthew." The Anchor Bible Series..

- Alfred Becker: “Franks Casket. Zu den Bildern und Inschriften des Runenkästchens von Auzon (Regensburg, 1973) pp. 125 – 142, Ikonographie der Magierbilder, Inschriften

- Brown, Raymond E. The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke. London: G. Chapman, 1977.

- Clarke, Howard W. The Gospel of Matthew and its Readers: A Historical Introduction to the First Gospel. Bloomington: *Chrysostom, John "Homilies on Matthew: Homily VI". circa fourth century.

- France, R.T. The Gospel According to Matthew: an Introduction and Commentary. Leicester: Inter-Varsity, 1985.

- Gundry, Robert H. Matthew a Commentary on his Literary and Theological Art. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1982.

- Hill, David. The Gospel of Matthew

- Levine, Amy-Jill. "Matthew." Women's Bible Commentary. Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, eds. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998.

- Powell, Mark Allan. "The Magi as Wise Men: Re-examining a Basic Supposition." New Testament Studies.

- Schweizer, Eduard. The Good News According to Matthew. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1975

External links

- Mark Rose, "The Three Kings & the Star": the Cologne reliquary and the BBC popular documentary

- John of Hildesheim, "History of the three Kings" modernized in English by H. S. Morris

- Alfred Becker, Franks Casket

- Caroline Stone, "We Three Kings of Orient Were"

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Documentary proofs: The census of Augustus and the first census (and taxes) of Publius Sulpicius Quirinius in the year 8 BC (in german)

- The Biblee

Categories: Christmas characters